We Were Wrong about Conspiracy Theorists

They aren't as prone to double-think as we once thought.

Nearly every study on the psychology of conspiracy theories will mention people’s capacity to accept contrary opinions simultaneously (i.e., double-think). By believing in one conspiracy theory, so it goes, you become more likely to believe in other conspiracy theories, even if they are contradictory. This finding traces back to a study that found that conspiracy-minded participants had a tendency to believe both that Princess Diana is still alive and that she was assassinated. This has been coined the “dead and alive effect”, and it has recently been cast into doubt.

A new study found that this effect was driven not by those who believe in two contradictory conspiracy theories, but by those who accept the official narrative and reject both conspiracy theories. Across 4 studies and a mini meta-analysis, the authors demonstrated that while disbelieving a conspiracy theory correlates with disbelieving another, the correlation between believing two contradictory conspiracy theories was unreliable and often negative. In other words, conspiracy-minded participants did not show signs of double-think, and if anything, they showed resistance to competing conspiracy theories.

How could the experts miss this, study after study and replication after replication? While scoffing at the conspiracy theorists’ capacity for double-think, they committed a cognitive fallacy of their own. Namely, they ignored the base rates of those who believe conspiracy theories and those who don’t. The latter far outnumber the former. Studies show that, though almost 50% of people endorse at least one conspiracy theory, the vast majority just don’t find most of them very convincing, especially after hearing them for the first time.

Say, for every 50 people who accept the official narrative, one person will endorse an alternative one. If you are looking for a correlation between the belief in contradictory conspiracy theories, and you analyze both believers and skeptics together, the skeptics are going to be far overrepresented. In other words, whatever the skeptics are doing, it is going to look like everyone is doing, because we are talking 50 skeptics against 1 believer. So in the infamous Princess Diana finding, the majority of participants weren’t saying “She is dead and alive”, they were saying “She died in a car accident, as reported by the officials.”

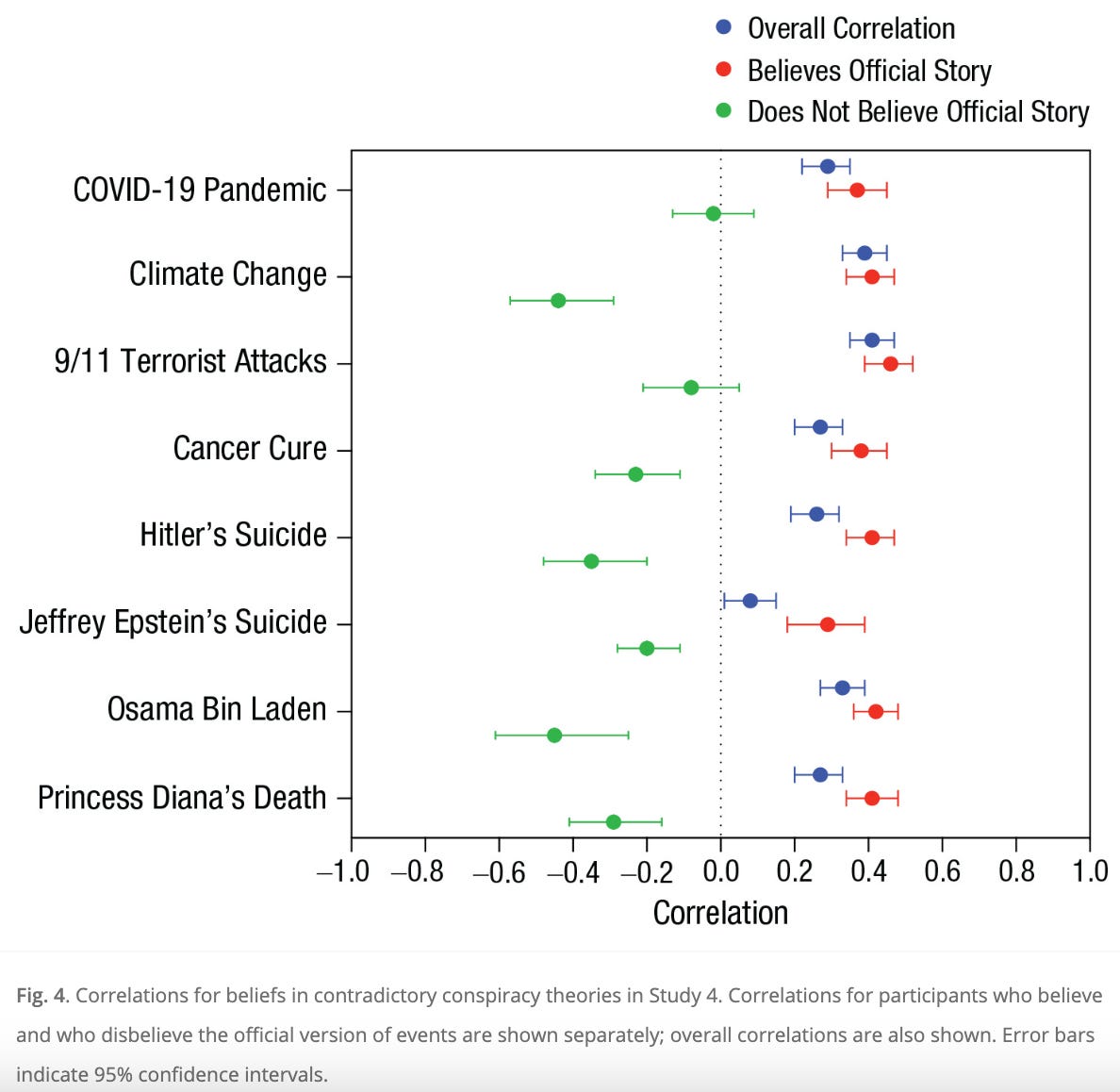

Here’s a figure from the paper:

If you are unfamiliar with data visualizations, this might take some squinting. Dots on the right denote a positive correlation (e.g., belief in one predicts belief in another), and dots on the left denote a negative correlation (e.g., belief in one predicts disbelief in another). As you can see, the overall correlation (blue) is mighty close to those who believe the official narrative (red), with those doubtful of the official narrative (green) nowhere in sight. Oh wait, there they are - they are on the other side of the chart, showing little influence on the overall correlation (blue).

Key takeaways? Believing the official story makes it more likely that you will reject contradictory conspiracy theories. Disbelieving the official story, if anything, makes it more likely that you will accept one and reject the other. I am avoiding speaking too strongly here because there really aren’t that many people who said that they reject the official narrative, so we can’t claim to know much about them.

What does this mean for the field of conspiracy theory research? Well, it is a direct challenge to the ‘monological worldview’ interpretation, which states that belief in one conspiracy theory predicts belief in others. Clearly, people are picky about their conspiracy theories. They don’t find them all equally compelling, especially if the conspiracy theory is specific or unfamiliar. It takes time to warm up to narratives that contradict the mainstream one.

It also calls for a more nuanced view of ‘the conspiratorial mindset’, which implies that if you have this particular mind virus, you will find conspiratorial explanations of events irresistible. It’s hard to know what exact factors are at play, but at the very least, the conspiratorial mind is much more complex than we once thought. It might be lazy, but it also shows skepticism - often too much skepticism.

It also means that those in the business of investigating human error, namely psychologists and behavioral scientists, are just as capable of human error themselves. This study provides a sobering reminder that we are all made of the same stuff, that we are all capable of lazy thinking, and that dismissing the “gullible” as merely gullible is unlikely to lead to an accurate picture of humankind.

Social

Twitter: @RyanBruno7287

Mastodon: https://mstdn.social/@ryanbruno

References

Brashier, N. M. (2022). Do conspiracy theorists think too much or too little?. Current opinion in psychology, 101504.

Oliver, J. E., & Wood, T. J. (2014). Conspiracy theories and the paranoid style (s) of mass opinion. American journal of political science, 58(4), 952-966.

van Prooijen, J. W., Wahring, I., Mausolf, L., Mulas, N., & Shwan, S. (2023). Just Dead, Not Alive: Reconsidering Belief in Contradictory Conspiracy Theories. Psychological Science, 09567976231158570.

Wood M. J., Douglas K. M., Sutton R. M. (2012). Dead and alive: Beliefs in contradictory conspiracy theories. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3, 767–773.