Pessimism and Credibility

Are pessimists more intelligent? If not, why do they seem that way?

It is thought essential for a man who has any knowledge of the world to have an extremely bad opinion of it.

~John Stuart Mill

When was the last time you turned on the news and got the sense that things just keep getting better? Likely never. More newsworthy are stories about war, viruses, crime, and so on. On the other hand, you will rarely hear a story about all the terrible things that didn’t happen yesterday. As is true with many things, no news is good news. Our inherent bias for negative information, paired with our demoralizing news cycle, leads us to believe that things are getting progressively worse over time.

Are things really that bad? Not really. At least 99 great things happened in 2021 alone. Or should we make it 192? 2021 was a year of tremendous progress, as were the years before it. Almost everything we care about is getting better and better (details in the footnotes).1 The data show that the pessimist is considerably and consistently wrong, at least on most things. So why do doom-mongers seem profound and wise, while optimists seem superficial and ignorant? Part of the answer lies in how we were built.

Unfortunate architecture

Pessimism has contaminated more than our news-cycle. It is also evident in the way we talk. To illustrate this, try to think of the positive equivalent of the word “trauma.” One might think of words like euphoria, self-actualized, transcendent, and so on. But these are far from perfect antonyms. To be traumatized is much worse than any of these antonyms are good. It is much easier to think of antonyms for positive words, such as depressed for elated, or chaotic for peaceful. Many studies have replicated the finding that our vocabularies are richer when describing negative phenomena. This may be one reason that pessimists sound so smart – they have access to a richer vocabulary. Our verbose negative vocabulary, paired with a limited positive vocabulary, supports the claim that bad is stronger than good.

To further evidence this point, reflect on how we make economic decisions. When presented with two scenarios of equal and opposite magnitude (e.g., winning $100 vs. losing $100), we perceive the loss as more salient. Though losing $100 is unlikely to kill anyone, consider a scenario that could:

You are a lone hunter-gatherer who has just obtained enough food for two days. You come across an animal that could supply you with enough food for 3 more days, but you will have to leave your food behind on the hunt. There is no guarantee that you will successfully kill this animal, but there is a risk of leaving your food behind to get snagged.

An overly optimistic hunter may leave his food behind to catch this animal, fail, and return to an empty hut. A strong aversion to losses allowed us to make the rational decision to stay put.

Consider another example regarding threats:

You are a hunter-gatherer collecting berries for your family. One bush supplies more than you can carry, so you decide to snack on as much as you can before you head back. You have indulged in about a handful before you taste one that is rancid and potentially poisonous. You immediately spit it out and discard all the berries you collected from that bush.

Even though most of the berries tasted fine, it is better to be safe than sorry. The threat of contamination is one of the fundamental reasons we experience disgust. It is why unpleasant odors can ruin an otherwise delicious meal.

Humans are, in a way, like smoke detectors. We would rather have our smoke detectors beep when there is no fire than fail to beep when there is one. This has been coined the “Smoke Detector Principle”. The evolutionary justification for this is that missing a positive outcome can only result in regret, ignoring a negative one could leave you maimed or dead. The structure of the brain vindicates this phenomenon. The part of the brain that is associated with attention (right inferior frontal gyrus) is the same region that gets activated when we make pessimistic judgments.

The Cynical Genius

Our inner smoke detectors can be applied to the social realm as well. Not believing someone who is trustworthy is fairly inconsequential – all you lost was a potential friend. Believing someone who isn’t trustworthy could lead to betrayal. This bias is what drives cynicism, the belief that people are motivated only by self-interest. Cynicism pays off, as the cynic doesn’t give himself the chance to get backstabbed.

Excessive error-avoidance often gets mistaken for superior judgment and hyper-realism. The pessimist’s perceived aptitudes in judgment get perceived as general intelligence by others. For example, negative reviewers are often seen as more intelligent (though, less likable), even when compared with higher-quality positive criticism. To criticize someone’s work is to imply that you could have done better, or at least you are clever enough to notice all of its flaws. To leave a favorable review is to admit that they did about as good as you could have.

The manipulative pessimist

Adding to their perceived self-assurance, blunt realism, and uncanny ability to read others, pessimists tell us things that we were already predisposed to believe. For example, most people already think that life is “nasty, brutish, and short”. Thus, a negative worldview could easily be taken for one that is informed by frequent encounters with our dark reality. The optimist hasn’t seen enough of the world, while the pessimist has seen too much, so it goes.

It is easy for an incompetent or uninformed person to leverage a melancholy worldview as a signal of their intelligence. A landmark study by Teresa Amabile shows that when people are making evaluations for a high-status audience, they will use negative evaluations to demonstrate their intelligence. Cult leaders and gurus alike take this idea a step further and suggest they are privy to the panacea.

Charles Manson prepared his followers for his doomsday scenario called “Helter Skelter”, where a race war would break out and kill nearly all white people. Jim Jones was obsessed with the idea of an inevitable nuclear holocaust. He led his followers to believe that he could see into the future, and thus save them from annihilation. David Koresh esteemed himself as the chosen one and built an “Army of God” to survive the impending apocalypse. Marshall Applewhite warned of a comet that would obliterate Earth, and the only escape was via UFO. The modern example of Alex Jones is almost too obvious to mention.

This level of pessimism isn’t exclusive to cult leaders. Even supposed secular gurus will sell portents of organized corruption and institutional decay. But don’t worry, they say, they know how to save us. Conspiracists will always exist, but we can be more resilient against their tactics by practicing to spot them.

The Cynical Genius Illusion

One of the reasons humans have made it this far is our innate bias towards cooperation. The most successful human societies are the ones that have found a way for everyone to work for everyone else. Look around your room. Everything in it was built for you. In exchange for these goods, you have devoted your time and energy to benefit society in your own way.

Cooperation and economic success have been linked in studies using trust games to show that people typically earned more if they were willing to trust one another. Cynical individuals earn less due to their ineptitude for cooperation.

It has also been suggested that optimism might be more prevalent in those who are more competent, who can see the good in the world for what it is, and who recognize that the risk of losing your life in modern times is fairly low. The adage “better safe than sorry” limits us only to opportunities that present minimal risk.

It’s not (only) the News’ fault.

Though our news cycle has a blatant bias toward negative stories, we cannot blame reporters alone. Part of the fault lies within the audience. Good news bores us, as it is often about things that aren’t happening. It is impossible to report the instances where something terrible could have happened, but it didn’t. Not only are these stories tough to report, but any attempt to do so would be seen as a minimization of suffering or failing to hold a wrongdoer accountable. If you haven’t visited the footnotes yet, I recommend you do so. Good news is everywhere, we just have to look at the data, which leads me to my prescriptive section of this newsletter:

Favor data over journalism.

Notice when other' interpretations are consistently negative. They may be using a pessimistic worldview to appear well-informed or to veil their incompetence in identifying real risks.

Don’t grant reputation credit to doom-sayers. Consider their points, and if time permits, use reliable, apolitical sources to investigate the data.

Pay attention to incentives. Is this person getting paid to spread negative information?

Ask for justification. That which is asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence (Hitch’s razor).

Recognize that negative news is much more likely to proliferate. Expect bad news, look for overall trends.

Remember that trusting others pays off.

Recognize when someone’s views can be reliably predicted. Are they prone to exaggerate every event as cataclysmic or as representative of a systemic issue? 2

Remember that most things are getting better. Remind others of this. Focus your energy on the things that have stagnated or are getting worse.

Cynicism masquerades as wisdom, but it is the furthest thing from it.

-Stephen Colbert

Twitter: @RyanBruno7287

References

Amabile, T. M. (1983). Brilliant but Cruel: Perceptions of negative evaluators. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 19(2), 146-156.

Cutler, I. (2005). Cynicism from Diogenes to Dilbert. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Fetchenhauer, D., & Dunning, D. (2010). Why so cynical? Asymmetric feedback underlies misguided skepticism regarding the trustworthiness of others. Psychological Science, 21(2), 189-193.

Hecht, D. (2013). The neural basis of optimism and pessimism. Experimental Neurobiology, 22(3), 173.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185.

Mercier, H. (2020). Not born yesterday. Princeton University Press.

Nesse, R.M. (2001), The Smoke Detector Principle. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 935: 75-85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03472.

Norton, M. I., Anik, L., Aknin, L. B., & Dunn, E. W. (2011). Is life nasty, brutish, and short? Philosophies of life and well-being. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2(6), 570-575.

Peeters, G. (1971), The positive-negative asymmetry: On cognitive consistency and positivity bias. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol., 1: 455-474. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420010405.

Rosling, H. (2019). Factfulness. Flammarion.

Rozin, P., & Royzman, E. B. (2001). Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personality and social psychology review, 5(4), 296-320.

Stavrova, O., & Ehlebracht, D. (2016). Cynical Beliefs about Human Nature and Income: Longitudinal and cross-cultural analyses. Journal of personality and social psychology, 110(1), 116.

Stavrova, O., & Ehlebracht, D. (2019). The Cynical Genius Illusion: Exploring and debunking lay beliefs about cynicism and competence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(2), 254-269.

Child mortality continues to decline.

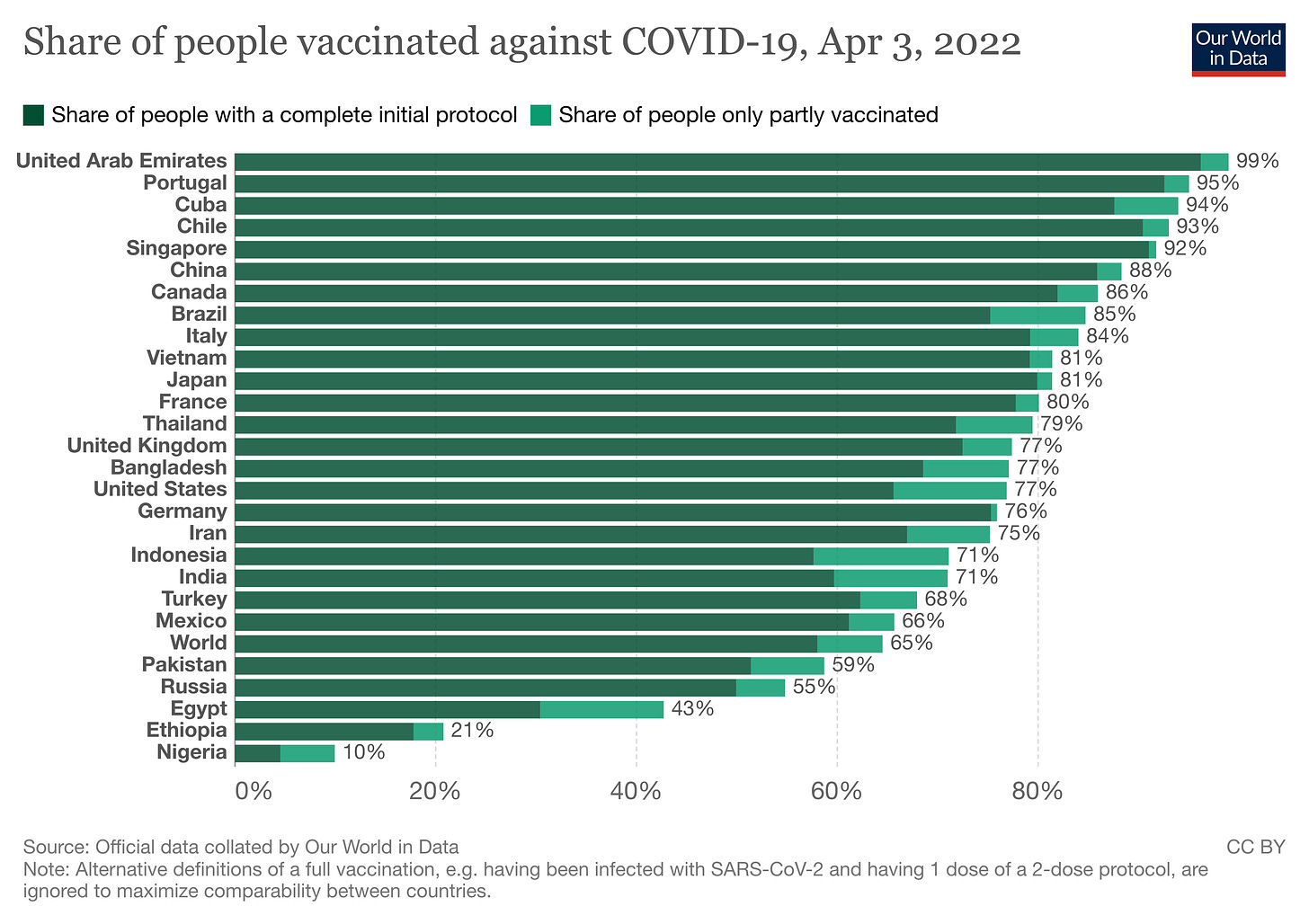

9 billion doses of the COVID-19 vaccine were rolled out in 2020.

Our world is getting richer and richer.

Racist hate crimes are declining.

The world is becoming more democratic (as opposed to autocratic).

The world is getting smarter.

For more trends, visit OurWorldInData.org or Unicef.org

To use a current example, the Will Smith slap invited a plethora of wild takes. Some attributed the slap to hundreds of years of anti-black oppression. Others described it as the inevitable conclusion of “words are violence”. Be wary of such hyperbolic takes.

Some good points in here. Checking out the linked papers. Definitely LOL at your optimism towards the covid vax.

BTW found your article through your reddit post. Good technique for bringing in readers to your substack.

https://www.reddit.com/r/psychology/comments/ug5yt7/article_on_how_pessimists_often_seem_more/